Snake Bites Cost Him Hundreds of Times. Now His Blood Is a Scientist's Dream.

Tim Friede has endured numerous snakebites—often intentionally. Scientists are now examining his blood with the aim of developing an improved antivenom therapy.

Friede has long had a fascination with reptiles and other venomous creatures. He used to milk scorpions' and spiders' venom as a hobby and kept dozens of snakes at his Wisconsin home.

Wishing to safeguard himself against snakebites and driven by what he describes as "mere curiosity," he started administering tiny quantities of snake venom into his system. Gradually, he escalated the dosage in an attempt to develop immunity. Afterward, he allowed snakes to bite him.

Are you looking for insights into the most significant issues and global developments? Find your answers here. SCMP Knowledge Our latest platform features handpicked content including explainers, FAQs, analyses, and infographics, all provided by our acclaimed team.

Initially, it was quite frightening," Friede stated. "However, as you continue doing it, your proficiency improves, and you grow increasingly composed about it.

Although neither a physician nor an Emergency Medical Technician – or anybody for that matter – would consider this even somewhat advisable, specialists indicate that his approach aligns with bodily functions.

When the immune system is exposed to the toxins in snake venom, it develops antibodies that can neutralise the poison. If it is a small amount of venom the body can react before it is overwhelmed. And if it is venom the body has seen before, it can react more quickly and handle larger exposures.

Friede has endured snake bites and injections for almost twenty years and continues to have a fridge filled with venom. In clips uploaded to his YouTube channel, he displays puffy puncture wounds on his arms caused by black mambas, taipans, and water cobras.

He stated, 'I aimed to test my boundaries as closely to death as feasible, getting so near that I was practically at the edge, before pulling back from it.'

However, Friede was equally eager to assist. He reached out via email to every scientist he could locate, requesting them to investigate the tolerance he had developed.

And there is a need: around 110,000 people die from snakebite every year, according to the World Health Organization.

Producing antivenom is costly and challenging. Typically, this process involves administering venom to big animals such as horses to elicit an antibody response, which is then harvested. However, these antivenoms tend to be effective solely for particular types of snakes. Additionally, because they originate from non-human sources, they may occasionally cause adverse reactions.

When Peter Kwong from Columbia University learned about Friede, he remarked, "Wow, this is quite extraordinary. We have an exceptionally unique individual who developed remarkable antibodies over 18 years."

In a study released on Friday in the journal Cell, Kwong and his team revealed how they utilized Friede's distinctive blood. They discovered two antibodies capable of neutralizing venoms from various snake species, aiming for potential future development of an inclusive antidote offering widespread protection.

The study is quite preliminary as the antivenom has only been tested on mice, with human clinical trials still distant. Although this experimental therapy holds potential for treating bites from elapids such as mambas and cobras, it does not work against viper species, including rattlesnakes.

“Even though there’s hope, significant work remains,” stated Nicholas Casewell, a snakebite researcher from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, via email. Casewell did not participate in the recent research.

Friede's path hasn't been free from mishaps. For instance, following a severe snakebite, he mentioned having to amputate a portion of his finger. Additionally, certain vicious cobra bites required him to be hospitalized.

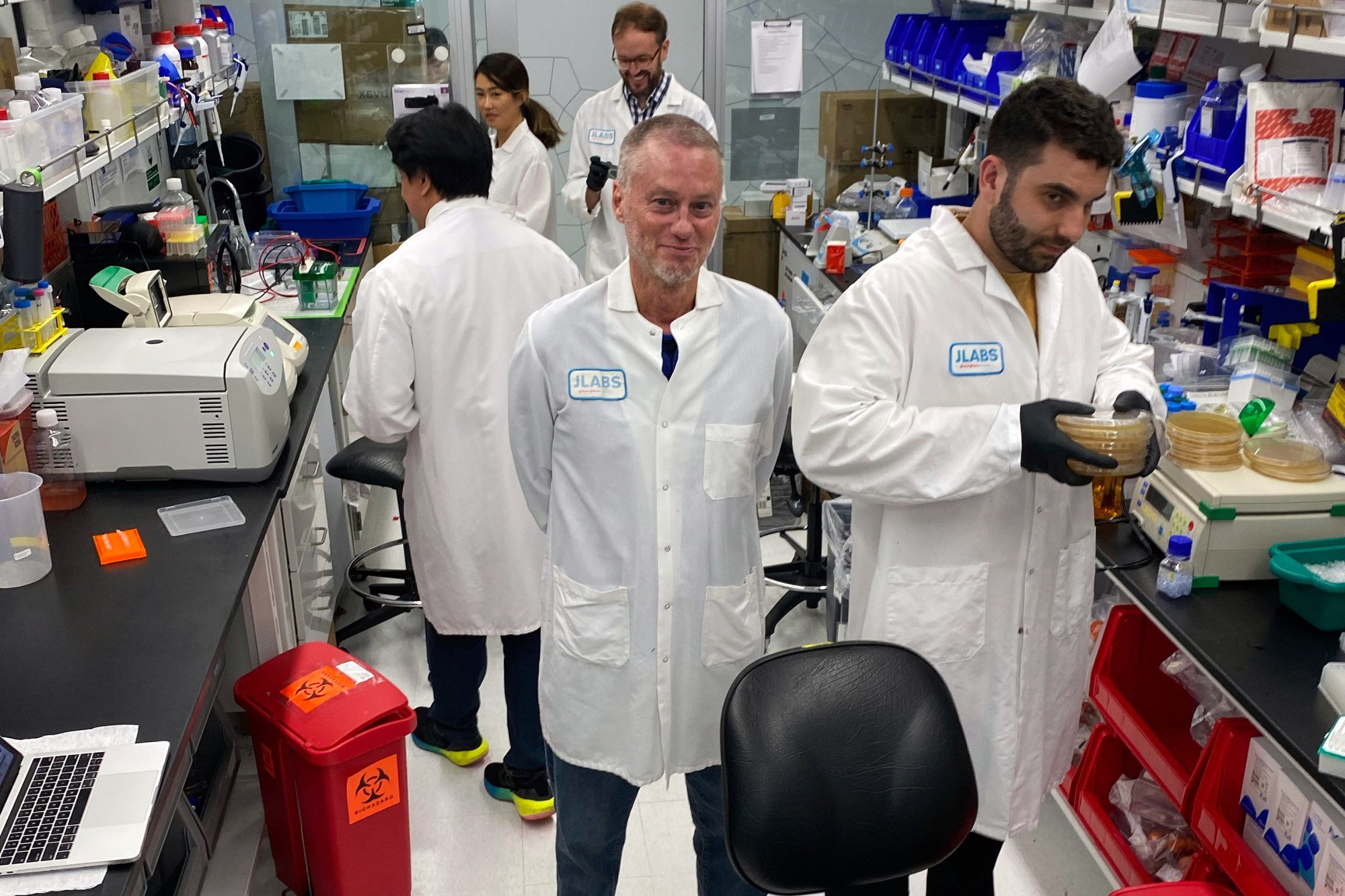

Friede is currently working at Centivax, a firm aiming to create the treatment and which also provided funding for the research.

He is enthusiastic about the potential of his 18-year journey to someday help prevent deaths from snakebites, yet he advises anyone contemplating following in his steps with a straightforward warning: "Don't do it."

More Articles from SCMP

Indonesia has become a new center for Chinese solar companies following Trump’s tariffs on Southeast Asian products.

China’s young talent scheme lures smart materials scientist Li Yongxi from US

The combination of Trump’s unpredictable nature and a divided United States creates a perilous situation.

China eases position on U.S. tariff discussions, condemns spying allegations: SCMP summary highlights

This article originally appeared on the South China Morning Post (www.scmp.com), the leading news media reporting on China and Asia.

Copyright (c) 2025. South China Morning Post Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.

Post a Comment for "Snake Bites Cost Him Hundreds of Times. Now His Blood Is a Scientist's Dream."